Put your future career first. Pay tuition when you're hired.

Pay $0 in tuition until you're hired in a qualifying position

Live, personal mentorship from industry experts

6 months of professional career coaching

Get a job in tech or get your tuition back.

We’re invested in your future. That’s why, if you don’t get hired in a qualifying position within 6 months of graduating, you get a full tuition refund. Find our terms and conditions on the Tuition Refund Policy here.

Our Programs

$17k average

salary increase reported by Thinkful grads

81%

grads report being hired in 180 days

4.8/5

Career Karma rating

1-on-1 mentorship

How we work

Get matched with a personal mentor who works in the industry.

Live, personal mentorship from industry experts

Detailed feedback and reviews

In-depth career services

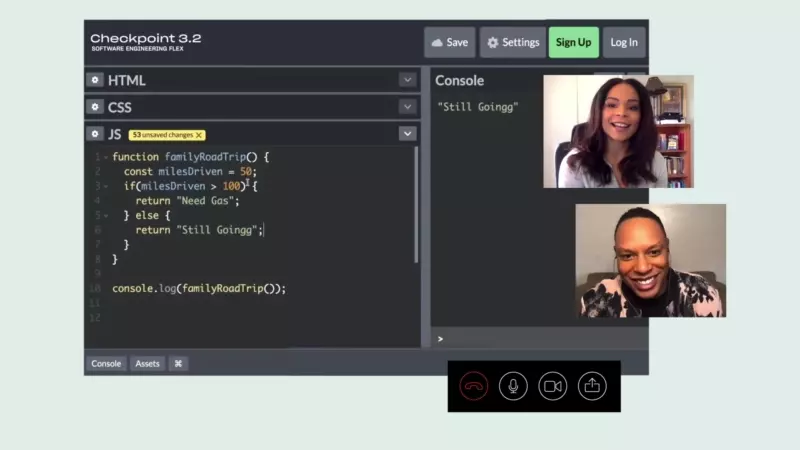

On-demand Technical Coaching

Connect with our expert educators in real-time with our live chat service. Ask questions and get feedback, fast.

Big names hire Thinkful grads.

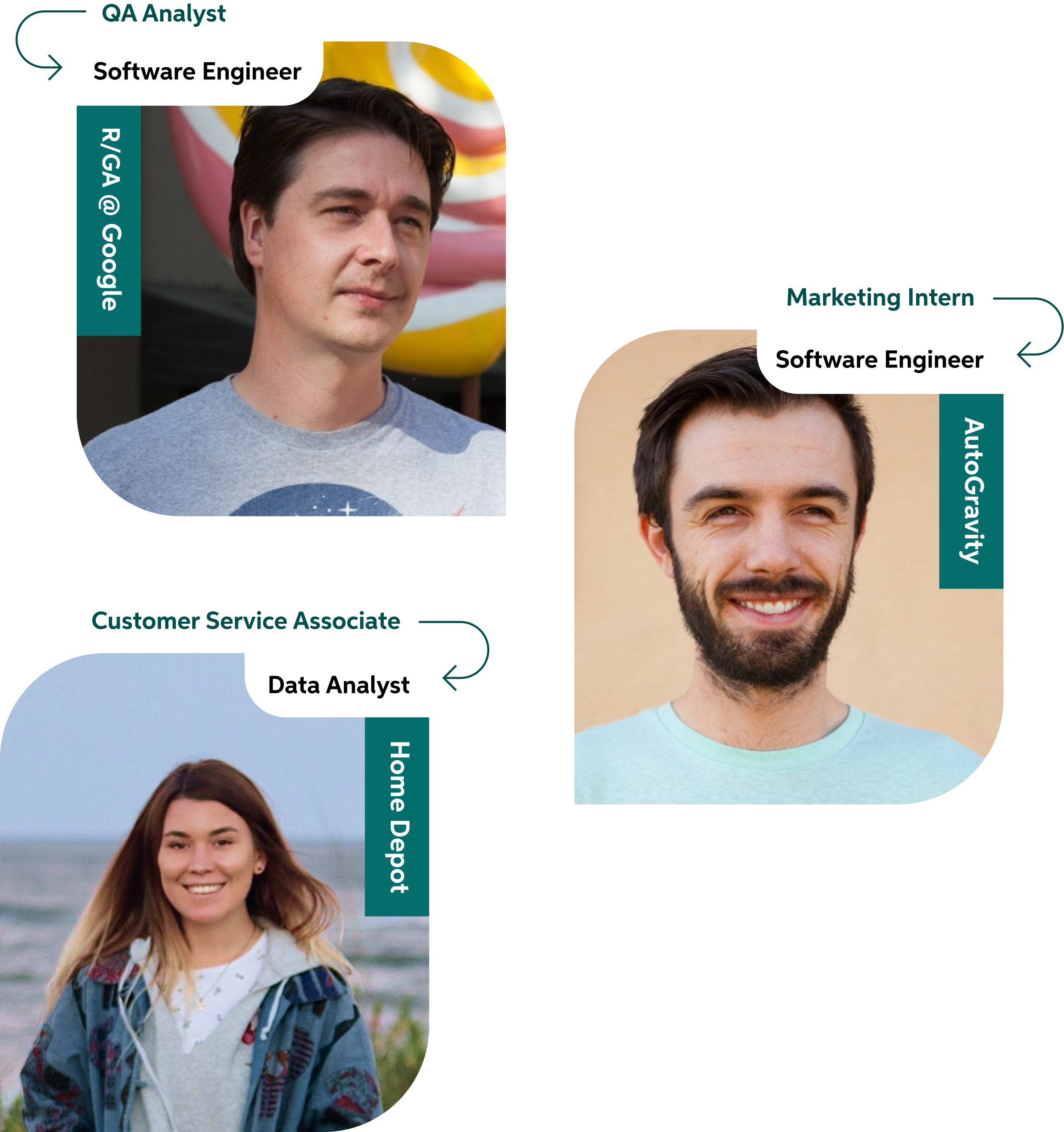

Student Outcomes

We help students launch careers.

Hired rate

81%

Average salary increase

$17K

Recent Job Offers

Our Admissions Team is here to help

We'll work one-on-one to answer your questions.